Discipline Specific Matrix Example – Theater

The Framework: We’ve drawn on two complementary approaches to conceptualizing information literacy to develop our model.

-

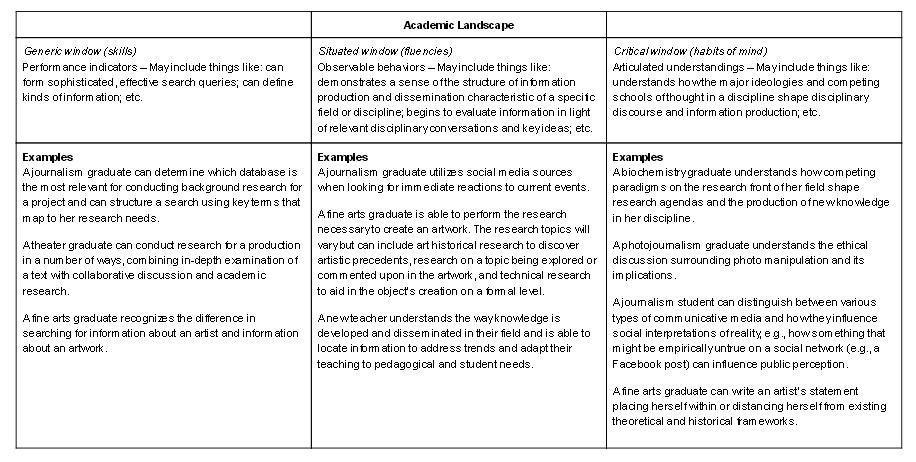

From Lupton and Bruce (2010) we borrow the notion that information literacy can be seen and described from three separate but related points of view — perspectives or “windows,” as they call them. The three “windows” they use to look at information literacy are the generic, the situated, and the transformative (or what we will call “critical.”).

-

From Lloyd (2010) we take the idea that embodied information literacy should be understood as occurring within socio-culturally created “landscapes” that “evolv[e]” over time into “intersubjective space[s]” of collective practice. Lloyd broadly defines three landscapes in which information literacy is commonly practiced: academic landscapes, workplace landscapes, and community landscapes, or what we here call the landscape of everyday life.

When these two frameworks are put together, a comprehensive look at information literacy emerges:

-

Looking at information literacy from the “generic” window, we are able to describe and define generic, measurable skills that we might say comprise information literate behavior of those at the early stages of information literacy skill acquisition who are learning the basic concepts of information literacy outside the immersive experiences of their major, workplace, or lives.

-

Looking at information literacy from the “situated” window, we are able to describe the socio-cultural competencies of those who have come to embody the information literate practices as exhibited within the context of real world academic, workplace, and everyday life practices.

-

Looking at information literacy from the “critical” window, we are able to describe the habits of mind that empowered members of communities exhibit when questioning, creating, and transforming the information and knowledge bases of the academy, the workplace, or other social communities to which they belong.

Unlike frameworks of the past, the matrices linked here are not “standards” that the CUNY colleges should strive to have their students meet. Rather they are descriptions meant to serve as a guide to help those in our University describe what information literacy looks and feels like to students at the point when they move into the next phases of their educations, whether formally in post-graduate study or informally within the workplace and other contexts of practice. Again, they help us depict, in analysis, what information literate students within the context of their own institutions might be able to do and how they might think when seeking and using information.

As such, the matrices developed through the process we’ve put forward should be used as a heuristic once completed — as a way into thinking about information literacy in the various contexts in which it is put into practice and embodied by a discipline’s students — and as a means for librarians and disciplinary faculty to describe for themselves what embodied information literacy looks like for their students in their various disciplines. They can be used as a prompt or jumping off point for librarians and disciplinary faculty in collaboration to design learning opportunities that enable students to meet disciplinary expectations. They can also be used to reframe and reposition the ACRL Information Literacy Standards, SCONUL Standards, and other formal analyses of information literacy within context-dependent descriptions of information literacy relevant to various institutional settings.